Unlucky Days (with footnotes)

that's XIII if you count in Roman

where bad luck may be known under a different cognomen (1)

the Seventeenth, since XVII can rearrange to VIXI (pronounced vixie)

which means "I HAVE lived"

and that could be considered something serious

in that realm once so VERY Imperious

and not just whistling Dixie(2).

So, as a result,

they thought Tuesday the Seventeenth was worse (4)

and even more likely to be under a curse.

Especially since their Tuesday, furthermore,

was named for the God of War

Mars --> Mardi, you see,

while if you are so tempted to inquire

our Friday celebrates a woman, Freya, (3)

the wife of (W/Odin and his Day is Wednesday--

not particularly noted for anything out of the way.

But perhaps here I'd better cease and desist

before I'll hear someone call me a sexist.

HzL

5/13/16

paraskevidekatriaphobia, from the Greek words Paraskeví (Παρασκευή, meaning "Friday"), and dekatreís (δεκατρείς, meaning "thirteen").

Cognomen - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- A cognomen was the third name of a citizen of ancient Rome, under Roman naming conventions. Initially, it was a nickname, but it lost that purpose when it became hereditary. Hereditary cognomina were used to augment the second name in order to identify a particular branch within a family or family within a clan. The term has also taken on other contemporary meanings.

(2)whistle Dixie

English[edit]

Etymology[edit]

Refers to the song "Dixie", the traditional anthem of the Confederate States of America. The full implication is that the Confederacy would not succeed in the American Civil War through sentiment or token action alone.

Verb[edit]

whistle Dixie (third-person singular simple present whistles Dixie, present participle whistling Dixie, simple past and past participle whistled Dixie)

- (idiomatic, Southern US) To engage in idle conversational fantasies.

- He said he was going to open a business next year, but I think he was just whistling Dixie.

- "Sure is hot!" / "You ain't whistlin' Dixie!

Usage notes[edit]

- Frequently used in the negative, to mean someone or something is serious, as in, When I say that, I'm not just whistling Dixie, I really mean it.

(3)

rom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Freya)

For other uses, see Freyja (disambiguation).

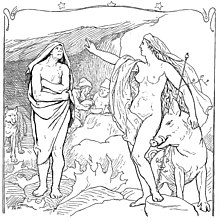

In Norse mythology, Freyja (/ˈfreɪə/; Old Norse for "(the) Lady") is a goddess associated with love, sex, beauty, fertility, gold, seiðr, war, and death. Freyja is the owner of the necklace Brísingamen, rides a chariot pulled by two cats, keeps the boar Hildisvíni by her side, possesses a cloak of falcon feathers, and, by her husband Óðr, is the mother of two daughters, Hnoss and Gersemi. Along with her brother Freyr (Old Norse the "Lord"), her father Njörðr, and her mother (Njörðr's sister, unnamed in sources), she is a member of the Vanir. Stemming from Old Norse Freyja, modern forms of the name include Freya, Freija, Frejya, Freyia, Fröja, Frøya, Frøjya, Freia, Freja, Frua and Freiya.

Freyja rules over her heavenly afterlife field Fólkvangr and there receives half of those that die in battle, whereas the other half go to the god Odin's hall, Valhalla. Within Fólkvangr is her hall, Sessrúmnir. Freyja assists other deities by allowing them to use her feathered cloak, is invoked in matters of fertility and love, and is frequently sought after by powerful jötnar who wish to make her their wife. Freyja's husband, the god Óðr, is frequently absent. She cries tears of red gold for him, and searches for him under assumed names. Freyja has numerous names, including Gefn, Hörn, Mardöll, Sýr, Valfreyja, and Vanadís.

Freyja is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; in the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, the two latter written by Snorri Sturlusonin the 13th century; in several Sagas of Icelanders; in the short story Sörla þáttr; in the poetry of skalds; and into the modern age in Scandinavian folklore, as well as the name for Friday in many Germanic languages.

Scholars have theorized about whether Freyja and the goddess Frigg ultimately stem from a single goddess common among the Germanic peoples; about her connection to the valkyries, female battlefield choosers of the slain; and her relation to other goddesses and figures in Germanic mythology, including the thrice-burnt and thrice-rebornGullveig/Heiðr, the goddesses Gefjon, Skaði, Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa, Menglöð, and the 1st century CE "Isis" of the Suebi. Freyja's name appears in numerous place names in Scandinavia, with a high concentration in southern Sweden. Various plants in Scandinavia once bore her name, but it was replaced with the name of the Virgin Mary during the process of Christianization. Rural Scandinavians continued to acknowledge Freyja as a supernatural figure into the 19th century, and Freyja has inspired various works of art.

Friday the 13th

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Friday The 13th)

This article is about the superstition. For other uses, see Friday the 13th (disambiguation).

Friday the 13th is considered an unlucky day in Western superstition. It occurs when the 13th day of the month in the Gregorian calendar falls on a Friday.

Contents

[hide]History

The fear of the number 13 has been given a scientific name: "triskaidekaphobia"; and on analogy to this the fear of Friday the 13th is called paraskevidekatriaphobia, from the Greek words Paraskeví (Παρασκευή, meaning "Friday"), and dekatreís (δεκατρείς, meaning "thirteen").[1]

The superstition surrounding this day may have arisen in the Middle Ages, "originating from the story of Jesus' last supper and crucifixion" in which there were 13 individuals present in the Upper Room on the 13th of Nisan Maundy Thursday, the night before his death on Good Friday.[2][3] While there is evidence of both Friday[4] and the number 13 being considered unlucky, there is no record of the two items being referred to as especially unlucky in conjunction before the 19th century.[5][6][7]

An early documented reference in English occurs in Henry Sutherland Edwards' 1869 biography of Gioachino Rossini, who died on a Friday 13th:

It is possible that the publication in 1907 of Thomas W. Lawson's popular novel Friday, the Thirteenth,[9] contributed to disseminating the superstition. In the novel, an unscrupulous broker takes advantage of the superstition to create a Wall Street panic on a Friday the 13th.[5]

A suggested origin of the superstition—Friday, 13 October 1307, the date Philip IV of France arrested hundreds of the Knights Templar—may not have been put together until the 20th century. It is mentioned in the 1955 Maurice Druon historical novel The Iron King (Le Roi de fer), John J. Robinson's 1989 work Born in Blood: The Lost Secrets of Freemasonry, Dan Brown's 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code and Steve Berry's The Templar Legacy (2006).[1][10][11]

Tuesday the 13th in Hispanic and Greek culture

In Spanish-speaking countries, instead of Friday, Tuesday the 13th (martes trece) is considered a day of bad luck.[12] The Greeks also consider Tuesday (and especially the 13th) an unlucky day[citation needed]. Tuesday is considered dominated by the influence of Ares, the god of war (Mars in Roman mythology). A connection can be seen in the Roman etymology of the name in some European languages (Mardi in French or martes in Spanish). The fall of Constantinople to the Fourth Crusade occurred on Tuesday, April 13, 1204, and the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans happened on Tuesday, 29 May 1453, events that strengthen the superstition about Tuesday. In addition, inGreek the name of the day is Triti (Τρίτη) meaning literally the third (day of the week), adding weight to the superstition, since bad luck is said to "come in threes".[dubious ]

Friday the 17th in Italy

In Italian popular culture, Friday the 17th (and not the 13th) is considered a day of bad luck.[13] The origin of this belief could be traced in the writing of number 17, in Roman numerals: XVII. By shuffling the digits of the number one can easily get the word VIXI ("I have lived", implying death in the present), an omen of bad luck.[14] In fact, in Italy, 13 is generally considered a lucky number.[15] However, due to Americanization, young people consider Friday the 13th unlucky as well.[16]

The 2000 parody film Shriek If You Know What I Did Last Friday the Thirteenth was released in Italy with the title Shriek – Hai impegni per venerdì 17? ("Shriek – Do You Have Something to Do on Friday the 17th?").

No comments:

Post a Comment